Justine Lloyd, Sydney

There is both the [horizontal and the vertical history], as it were, that we might attach ourselves to when we start to meditate on a city… There’s the history that seems to be unfolding and moving forward, and there’s the plunging down into the interiority of the place, into its lost histories.

Gail Jones interviewed by Gail Wachtel, 2012, quoted in Wolfe (2016: 46)

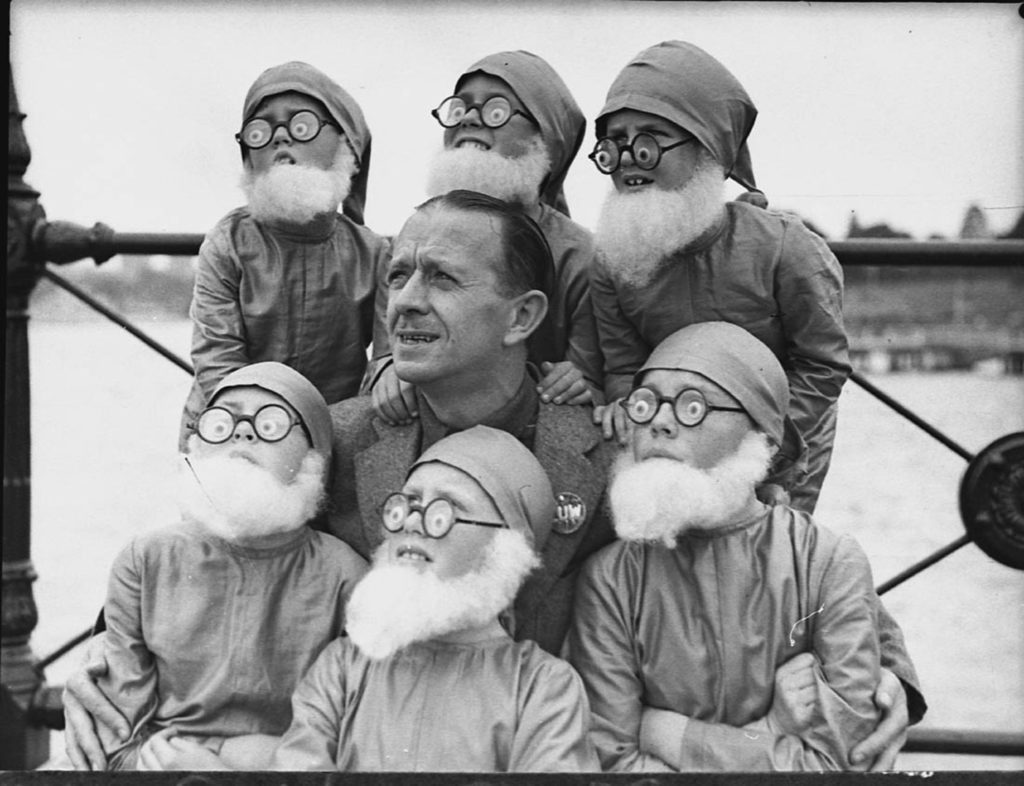

This photograph taken by Sam Hood, the prolific Sydney commercial photographer, of a harbour cruise to promote a children’s program on commercial radio in October 1937, tells a fascinating story about how the use of radio for outside broadcasting has been intertwined with histories of Sydney’s harbour (Figure 1). This essay (in two parts) uses media history as a sounding tool. I use media objects from two very different periods and of two very different activities as ‘sounding tools’ to explore the contours of representations of the harbour. As Australian novelist and literary scholar Gail Jones suggests, there are histories that are sedimented in the layers of emotions, images and text accrued at certain sites. These muddied, non-linear histories rise up when place itself is interrogated through its mediatisation.

In this aspect, I am interested in how the site of the harbour has been mediated and mapped by radio in two key periods: the first in the 1930s when radio was allied to domestic space and new audiences, such as young people were being called to listen to regularized programming within pre-determined social categories of family and childhood, and an earlier moment in the 1920s, when radio listeners were imagined to be individuals who were invited to explore new territories opened up by wireless, telephonic, engineering and transportation technologies. By tracing how the city’s maritime history has been mediated through sonic and visual representations, we can better see how port cities such as Sydney contain deep historical layers of connections to other places through exploration and travel. As we suggest in this series of interlinked ‘Harbour Cities’ essays, transportation and communication networks both negate and depend on place. We can also see how some of these connections between place and media have been promoted and valorized in public memory, while others are ignored and deflected in official narratives of progress.

While radio during the 1920s and 1930s was venturing into places that had not previously been networked within broadcasting, the media events described here opened up new liminalities, especially between the home and the city, the terrestrial and the littoral. In parallel with what Tom Gunning (1986) has called a ‘cinema of attraction’, such radio presented coverage of exotic and unfamiliar places in a disconnected sequence of audio images as a ‘soundscape of attraction’. Gunning explains that early cinema used the medium “less as a way of telling stories than as a way of presenting a series of views to an audience, fascinating because of their illusory power (whether the realistic illusion of motion offered to the first audiences by Lumière, or the magical illusion concocted by Méliès), and exoticism” (Gunning 2016, p. 382). While the first steps of radio into the world of the senses were not only addressed to a single (male) listener, listening via a home-made crystal set remote from the scene, rather than a collective audience located in cinematic infrastructure, a key difference of radio during the 1920s and 30s from early cinema during the early 1900s was radio’s unique element of ‘liveness’. This potential for remote auditory experience in real time is explored in both parts of this essay, the first of which was a children’s cruise with singing goblins.

Sounding One, 16 October 1937

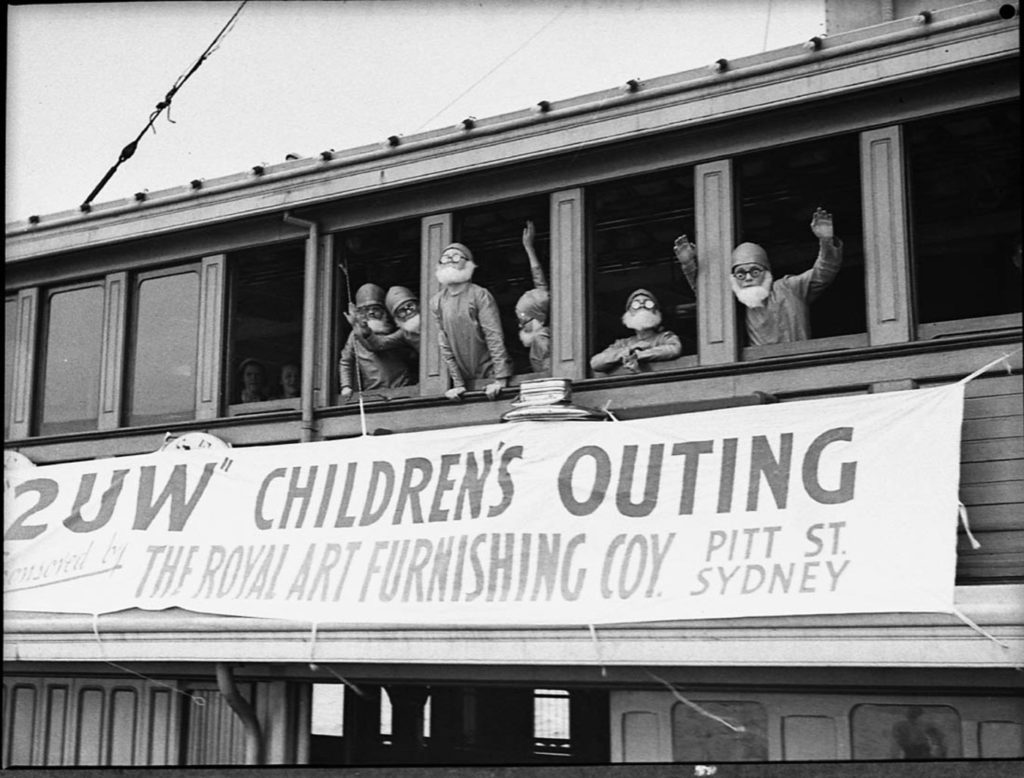

Hood’s photographs above [Figures 1 and 2) document a ‘Children’s Outing’ which took place on a spring Saturday in Sydney in 1937. The event was sponsored by the Royal Art Furnishing Company—“Sydney’s Cheapest Bedding Store”, according a 1934 advertisement in the Sydney tabloid, The Sun (‘Sensation: Colossal Furniture Purchase’ 1934)—located at 280-282 Pitt Street, close to the Circular Quay ferry terminal at Sydney Cove.[1] Taking place at the height of the economic depression of the 1930s, this harbor outing was designed to raise money for the Camperdown’s Children’s Hospital and was organized and promoted by commercial radio station 2UW. Following the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932, the use of watercraft for commuter transport became less popular and thus less viable, and these kinds of ferries ‘outings’ and cruises that toured the harbour rather than simply crossing it were popularized by ferry operators.

The event also took advantage of the technical opportunities for broadcasting live from outside the radio studio that had existed in Australia since the late 1920s. Socially, these kinds of broadcasts linked an audience ‘at home’ with public gatherings in church services, meetings and congresses. The ‘Children’s Outing’ was not just a networked public event, however, but also a highly mobile space, made possible by radio as part a technological complex at the intersection of advertising, shipping, media and domestic design industries.

During the outside broadcast, the audience at home was invited to experience the harbour trip and on-board entertainment. The placement of 2UW’s children’s session within its Saturday schedule for forty minutes from 5pm stands out against the station’s backdrop of live racing ‘talk’ and reports for nearly ten hours a day, from 9.30am until 7.15pm daily (‘Broadcasting’ 1937). The broadcast incorporated live radio theatre and music, thereby reshaping domestic space and time to include public performances. The passengers on the ferry were themselves also able to see and hear radio being produced live. The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate, published twice-weekly in Parramatta, then part of the rural edge of the city of Sydney, reported that the

actual children’s session will be broadcast whilst the steamer ‘Kattabul’ [sic] is cruising… [and] an episode of Uncle Tommy’s [2UW Children’s Session host, Tom Hudson] serial play, “Jimmy and Jean,” is being acted before the microphone on the ship, thus enabling everyone to see the child artists of 2UW at work.

(‘Harbor Outing for 2UW Children’ 1937).

Figure 3: 2UW (1937, June 25). Top Speed Express to the Magic Land of Make Believe. The Wireless Weekly: the hundred per cent Australian radio journal, p.34. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-707706170

Ever on the lookout for visual interest and urban curiosities, Hood photographed the radio session’s supporting characters: “six little goblins from Gnomesville [who] will be in attendance on the guests and will broadcast one of their famous songs during the afternoon” (Figure 2) (‘Harbor Outing for 2UW Children’ 1937). The ‘little goblins’ were featured characters in a regular ‘Gnomesville’ spot on the Children’s Session, which was portrayed in advertising as a “top speed express to the magic land of make believe” (Figure 3) (2UW 1937). The use of harbor expeditions as a means of the promotion of radio programming for families continued into the 1940s, with radio station 2CH, a commercial station owned by the NSW Council of Churches, promoting branded ‘Jolly Boat’ cruises featuring community singing led by station personalities (‘Anniversary Cruise of 2CH Jolly Boat’ 1941).

[1] Sydney Cove was named after the colonial administrator Thomas Townsend, 1st Viscount Sydney, who was Home Secretary of the British Government at the time of the first fleet. The traditional owners of the site, the Cadigal people of the Eora nation, called this small bay with a deep anchorage and a fresh water stream Warrane (also recorded as Warrang) (Attenbrow 2009). Townsend was responsible for the plan to colonise New South Wales after the US declaration of independence. Thus these ascriptions of colonial toponymy at key sites in the harbour—and the landmarks and access points of the Australian coastline more generally at this time—were acts of territorialisation, inscribing the political personae of the British empire over the landscape. In doing so, colonisers enacted a linguistic form of dispossession by overlaying European signifiers on the site, which disrupted, but not overturned, enduring Indigenous cultural practices connected to such material sites.

End of Part 1…

To be continued in an upcoming post on this blog: Harbour Cities: Sounding Sydney Harbour: radio explorations above and below the surface: Part 2