Victoria Knight, Justice and Society, University of South Australia

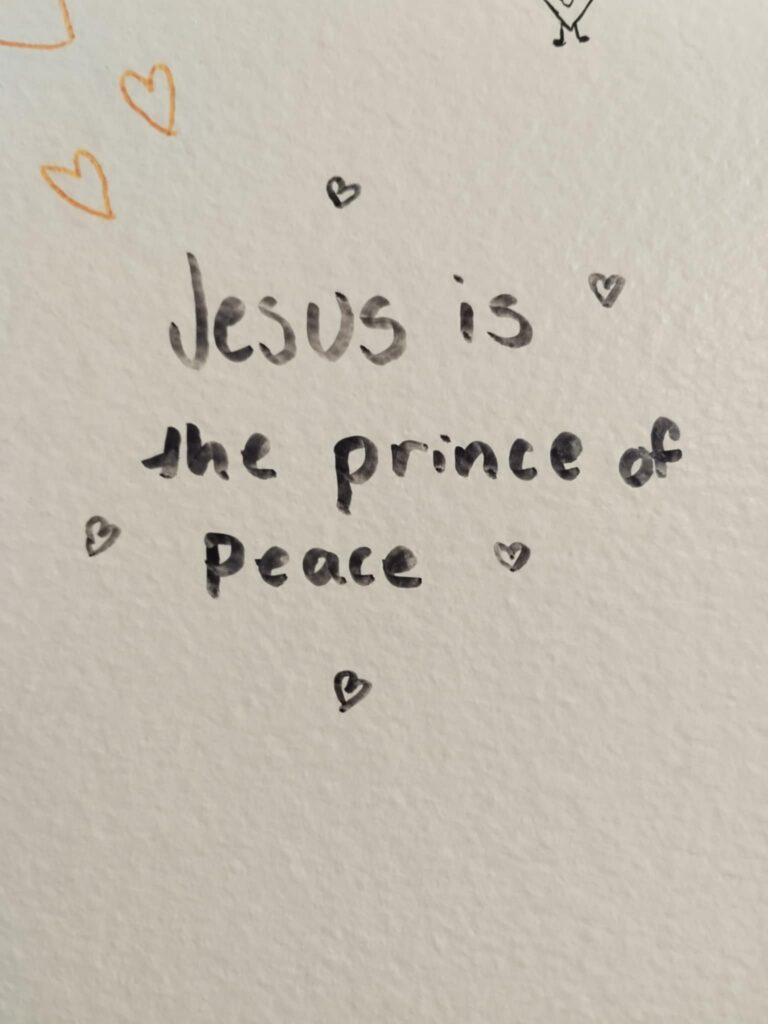

Jesus is the prince of peace.

I read the words immediately because I have to turn sideways to fit through the stall door. The message is graffitied on the stall wall along with several hearts. Someone enters the stall beside me as I wriggle uncomfortably out of my overalls, grazing both sides of the stall with my elbows and hands. I try not to think about the bacteria I pick up as I sit down, but it’s difficult when my knee jams against the toilet paper roll holder and the back of my hip is cut into by the sanitary waste unit. I’m sure there will be a red divot in the soft flesh above my ass, but I won’t be able to see it, because there’s scarcely enough room for me to piss in here, let alone to perform self-diagnostic contortion.

I’ve been in bathrooms that have smelt worse, in fairness. There is a faint eau-de-urine but considering the room’s purpose, that’s to be expected. There are sounds of washing hands and shuffling trousers and pads being ripped off of cotton gussets.

After I’ve managed to pee, I lean back against the sanitary waste bin as if it my partner in a long labour, except instead of childbirth it is the labour of spreading my too-large-thighs wide enough for me to perform that all-too-luxurious act of wiping myself that frankly, I am audacious to think myself worthy of trying to do in this stall. It whispers to me that I am too large, and I wonder what it says to those larger than me, to those less-abled than me, to those who might need more than 3/8th of a fuckall inch to wipe their goddamn ass.

I do not need to wonder, however, about the response to the welcome graffiti. As I flush and right my clothes, I reassume the position, ready to gracelessly crab walk out of the stall, and I see the response to the exaltation of Christ’s peace-bringing power below it in scratchier, smudged writing.

![Smudged and very hard to read graffiti drawn on a surface that reads "No tf he ain't LOL" [i.e. presumably 'Not if he ain't, LOL', in reference to previous graffiti saying 'Jesus is the prince of peace']](https://www.spaceandculture.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Image-2-No-tf-he-aint-LOL-768x1024.jpg)

No tf he ain’t LOL

When presented with this idea of walking/writing through fields of power, my first thought centred on what it really means to pass through space. Where through-ness may evoke an unencumbered fluidity for some, for me, it evokes planning. It evokes breaks to sit or lean and catch my breath. It evokes getting stuck, needing to reroute, abandoning journeys to wherever through ended up entirely.

Practices like walking which are considered everyday by some people are in reality laden with multiple meanings and implications for others. The breadth of inaccessibility and the actions and practices that the able-bodied world takes for granted is almost inarticulable, but for this writing exercise, I honed in on my own lived experience as someone in an ambulant fat body, and a place which occupies a particularly unassuming and often unconscious part of everyday—the public bathroom stall.

In articulating the role of the experiential in place-making, David Seamon states that:

places are multivalent in their constitution and complex in their dynamics. On one hand, places can be liked, cherished, and loved; on the other hand, they can be disliked, distrusted, and feared. For the persons and groups involved, a place can invoke a wide range of supportive, neutral, or undermining actions, experiences, and memories.

(Seamon 2018, p. 2)

This multivalence of place, I argue, becomes particularly noticeable in a place like the public bathroom. For most people, it is a decidedly neutral place, if not one with certain associations with mild disgust depending on the bathroom’s upkeep. For me, as a fat person, the public bathroom is, at best, a place of negotiation. I try to select middle stalls, as end stalls will often have jutting out sections of wall to encroach on my space, or the stalls might be a few millimetres smaller in an architectural attempt to fit in one extra stall each side for the populus who might access this bathroom. I almost invariably turn to the side to fit through a stall opening, as I can suck in my stomach if I need to, but I cannot suck in my broad shoulders or thick arms. I have to assess whether I have room to use the stall before I commit to anything, not wanting to be caught out, vulnerable and stuck in a space so clearly not made for my body.

Places—and the objects within those places—are not neutral constructions. They are the result of normative standards, desires and directions which go largely unchallenged and unnoticed by those who are not excluded by their design. Sara Ahmed (2006) posits this in her exploration of “queer phenomenology,” wherein she further examines how othered bodies are positioned as “out of line” with the normative Western standards that are produced and reproduced in everyday places. The dimensions of public bathroom stall doors or the room left around toilet paper dispensers and sanitary bins are not standardised around a fat body, a fact which I as a fat person am acutely aware of each time I enter a bathroom stall. I am reminded of the lack of consideration for fat bodies with the physical press of the objects in a public bathroom against my fat body – as Negus (2021) states, “spatial barriers impress upon fat guts: the fat body does not fit” (p. 210).

Being in a fat body means that my path through is typically not smooth or unencumbered. Often, it requires careful negotiation of places that most people can move through without a second thought. By understanding that places as pedestrian as the public bathroom are still constructed and multivalent, however, we might begin to think twice about those places and practices we take for granted, and what it really means to be able to smoothly and freely move through spaces, places and our everyday life.

Ms Victoria Knight

victoria.knight@mymail.unisa.edu.au

Acknowledgements: This work was completed on Kaurna land, where I live and work. I pay my respects to Elders, past and present. This always was, and always will be, Aboriginal land.

About the author: Victoria Knight is a PhD candidate at the University of South Australia whose research centres on fat queer lived experience through phenomenological and affective lenses. Their research interests largely lie at this intersection of fatness and queerness, with a particular interest in bridging the gaps between fat queer lived experience, academia and activism.

Works Cited:

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Duke University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822388074

Negus, C. (2021). A Gut Feeling: Towards a Fat Phenomenology. In T. Hiebert (Ed.), Casual Encounters, Catalyst: Cindy Baker (pp. 203–218). Noxious Sector Press. https://www.noxioussector.net/press/Hiebert-CasualEncounters.pdf

Seamon, D. (2018). Life Takes Place (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351212519