Elena Siemens and MLCS 210 Mappers

Shot from the 34th floor of my hotel room in Honolulu, the swimming pool appeared more like Aladdin’s magic lantern. My jet-lag might have contributed to this as well.

Aerial photography, Mary Warner Marien writes, “was first invented in the human imagination,” its early examples dating from the 16th century (Warner Marien). In more modern times, aerial photos came to dominate “military, scientific, and commercial” practice (Warner Marien). This perspective’s “mind-altering patterns” also attracted such early twentieth-century artists as Piet Mondrian who “picked up on abstract designs that appeared in aerial photographs of his native Holland” (Warner Marien).

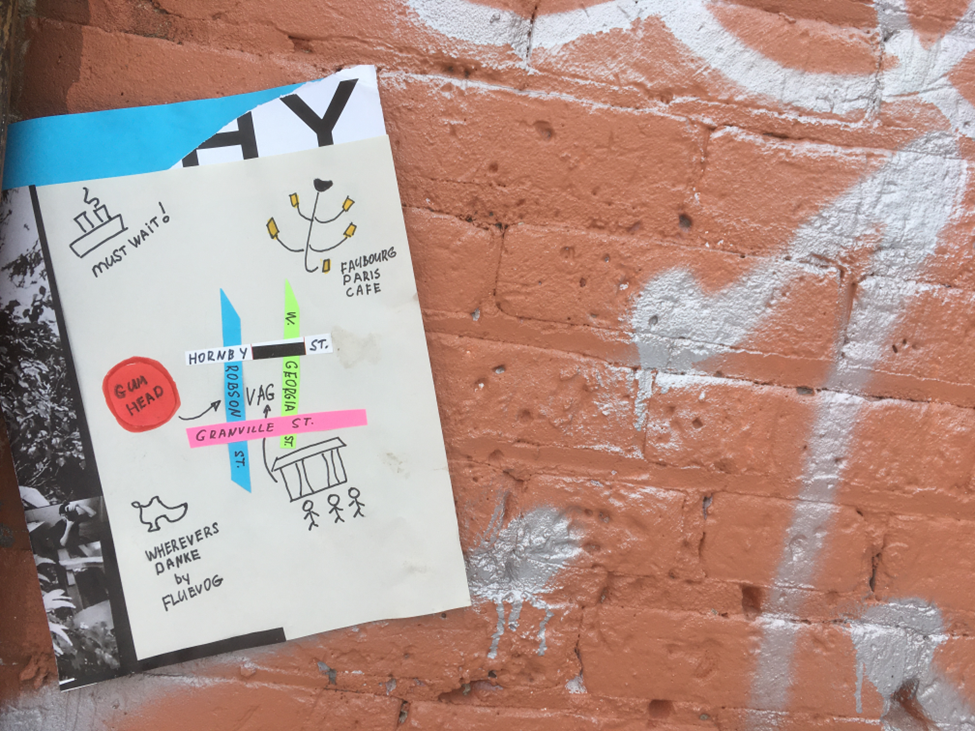

Created as a sample for a student assignment in a cultural studies course, this improvised map depicts some of my personal landmarks in Vancouver. Here, the harbour and the Faubourg Paris café appear in close proximity which does not exactly correspond to reality.

“A part of what makes public art interesting is how it interacts with its immediate environment,” Keri Smith points out in Guerrilla Art (Smith). Her prompt “Map of the Area” instructs the reader: “Either draw a map of the area you wish to post in or use an existing map,” indicate “your favourite points of interest on the map – nice place to sit, favourite tree, good burritos, etc.,” and then “Go to your location and hang the map” (Guerrilla Art). For our course purposes, everyone was free to depict any location around the world they choose for their personal reasons.

Ariana Valacco: “I picked Venice as a city because it is very important to my heritage. […]. I also find my trips to Venice as significant events in my life as I was exposed to cultural and religious spaces filled with art.”

In contrast to the “Map of the Area” prompt as outlined in Guerrilla Art, students were not required to leave their maps outdoors. Rather, everyone photographed their map at their chosen location and then collected it to share in class. This way you still faced a group of spectators, although a more familiar one. Nevertheless, revealing your personal map in class represented a challenge, in some cases more than in others.

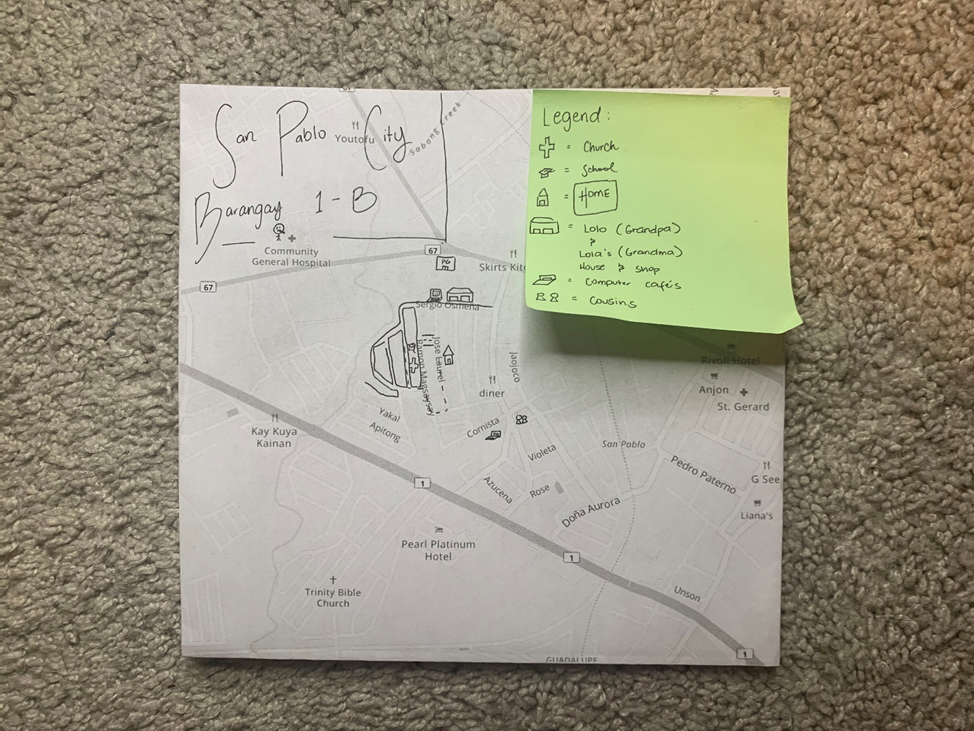

Romar Dungo: “Leaving tangible belongings behind, leaving personal relationships behind, leaving my future in my home behind. I still recall the day my family left the Philippines. I remember the overpouring of emotions – it was a day for grieving.”

In Paris 48°49N 2°29E, Ami Sioux documents a collaborative project for which she asked “50 inhabitants of Paris […] to hand-draw a map to a place that was important to them” (Sioux). She then “would use the map to find the location and photograph it” (Sioux). She explains: “Each time I arrived at a destination, I would study the area, looking at each map […], and then I would work to photograph in a way that emanated either the map or the reasons I felt the person was drawn there” (Sioux).

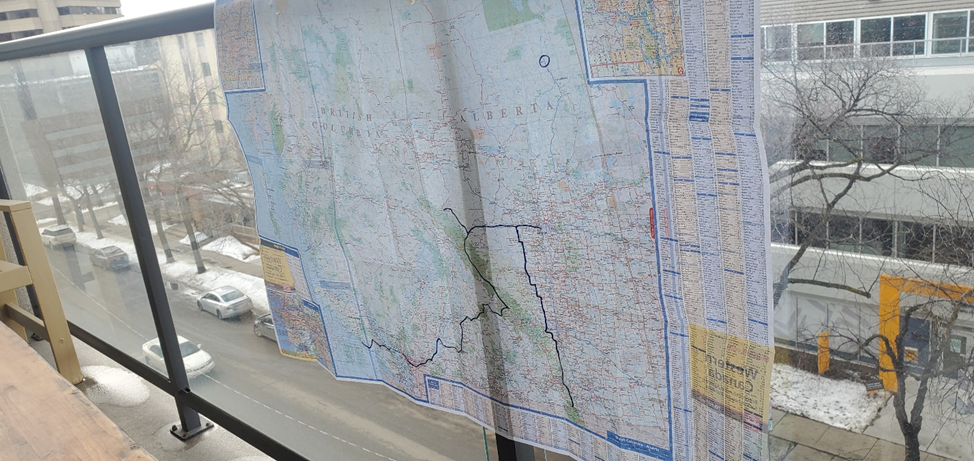

Sanjam Mann: “A closer look at the map itself reveals 3 distinct red spots. One in India, one in Edmonton’s core and one in North Edmonton. […]. I named the map insanity because once we consider how unique each soul walking the streets is, how unique each interaction is, we realize our own perfect little insanities.”

Documenting her Paris project, Sioux refers to Guy Debord and his fellow Situationists, who in the 1950s advocated the practice of the dérive, or wandering in the streets with no particular intention. The dérive served as Sioux’s guide: “Each person wrote down what influenced their decision, and I would use these clues towards my own discovery, but the relationship between the map and the photograph became the final structure of the ‘portrait’ of each person” (Sioux).

Logan Mahoney: “I just know that as soon as I depart on my motorcycle for one of these trips [outlined on my map] I will immediately feel the wind breaking off the stress accumulated from a long winter indoors.”

In our case, students themselves took photos of their maps. Everyone was free to choose what to capture and to cut out, whether to photograph it in color or in black-and-white, make it subtle or bold. The “final structure” was entirely their own. This approach was more akin to the détournament – another provocative strategy advocated by the Situationists.

The Situationists called upon “people to adorn the streets with statements such as ‘Free The Passions,’ ‘Never Work,’ ‘Live Without Dead Time,’ and ‘It’s Forbidden to Forbid'” (Cedar Lewisohn). They also “inspired people to rework or détourn metro posters, thus being an early prototype of what we now call ‘subvertising'” (Lewisohn).

Leaving Honolulu twenty-four hours later, I took a farewell photo of the neon marquee on the roof of the Daniel K. Inouye International Airport. If I were to make it, my map of Honolulu would be a case of the détournament as well. It would include just two landmarks: that magic-lantern swimming pool at the hotel, and the airport’s neon sign.